The impact elections can have on investments – Market Briefing 60

14.08.2024In this issue, we take a look at the impact elections can have on investments.

Emotions have the potential to lead rational investors to make irrational choices. Significant events such as general elections can impact investors, including stock market traders, and could influence their reactions.

Using the UK as an example, we will explore the impact a general election has had on the markets in previous years.

Headlines – the year of the ballot box

The UK is not alone in having elections.

In what has been described as ‘the year of the ballot box’, 2024 has seen and will see other nations with General Elections. Around half the world’s population in more than 60 countries are holding General Elections this year; a total of approximately two billion eligible voters.

The world’s most populated country (1) went to the polls earlier this year with more than 960 million people out of a population of 1.4 billion people eligible to vote. Following a seven-week campaign, Narendra Modi won his third term as Prime Minister of India in June.

There are also elections to the European Parliament but the most high-profile election this year will undoubtedly be in the U.S. in November.

Returning to the UK, it’s been around a month and the dust has settled on the 2024 general election, with the Labour Party sweeping to power after 14 years in opposition.

Winning a historic 411 seats – only one more than the exit polls predicted hours before – the Keir Starmer led Labour Party has a working majority of 181 seats, the largest majority in 192 years since the Whigs defeated the Tories in the 1832 election. In terms of number of seats, it’s the largest in exactly 100 years, when the Conservatives defeated Labour in the 1924 election.

Some big names from the Conservatives all suffered their own ‘Portillo moment’. Westminster Cabinet members, Grant Shapps (UK Defence Secretary) and Gillian Keegan (Education Secretary for England) both lost their seats, whilst other prominent Tories such as Penny Mordaunt, Jacob Rees-Mogg and former Prime Minister Liz Truss, also suffered defeat. In a remarkable night, five Tory Welsh Secretaries of State all lost their seats; Wales ended the night with no Conservative MPs.

Former prime minister, and now leader of the opposition, Rishi Sunak, retained his seat but resigned as Tory leader, paving the way for the election of the fifth Conservative leader in less than a decade. Kemi Badenoch, James Cleverly, Robert Jenrick, Priti Patel, Mel Stride and Tom Tugendhat have ‘thrown their hats into the ring.’ Following campaigning and a final pitch at the Conservative party conference, four will be shortlisted by MPs in September. MPs will then narrow to two candidates, with members electing the next leader in early November.

The SNP suffered catastrophic losses whilst the Liberal Democrats ended the night with over 70 MPs, and Nigel Farage, leader of the Reform UK party, won for the first time after seven unsuccessful previous attempts. Although Reform received over four million votes, he will only be joined by four party colleagues; an inevitable debate regarding voting reform is likely to follow. The Green Party won 4 seats and received almost two million votes. Undoubtedly, the House of Commons will look starkly different than it did before.

The economic question, however, is how do elections impact long-term investing?

Election impact on long-term investing

Emotions can turn logical investors into irrational people. Significant events such as general elections can have an impact on investors. As well as individuals, investors include stock market traders, all of whom feel emotions and can react accordingly.

So to answer the ‘so what’ question posed above, how do elections impact investing?

UK elections since 1987

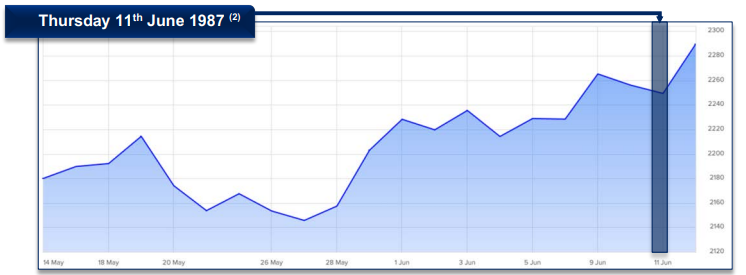

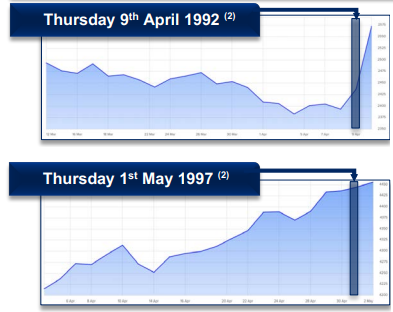

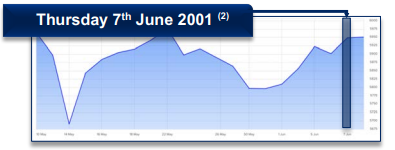

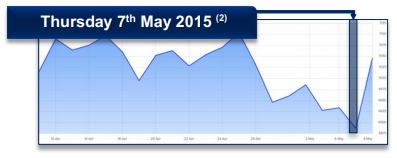

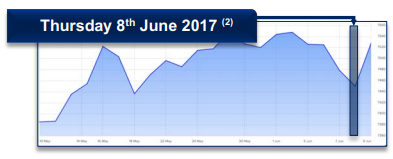

Using the UK as an example, the graphs below will examine a main UK stock market in and around the month of a general election.

Since 1987 – the year of the ‘Big Bang’ in the City of London – there have been ten general elections to the House of Commons at the Palace of Westminster. During this period, the Conservative Party has won five elections, the Labour party four and 2010 saw no outright majority leading to the Coalition government comprised of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. All but one of these elections occurred between 9th April and 11th June in the year it was held; the 2019 election was on 12th December.

Margaret Thatcher won the last of her three election victories on 11th June 1987, beating Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party with a majority of 102 seats. As can be seen from the graph above, which covers the period 14th May to 12th June 1987, i.e. the month before the election plus one day after it, the UK’s leading stock market didn’t react in any particular direction, perhaps fuelled by the expected result, it ended on Friday 12th June slightly up. So nothing much to see here. Later in the year however on 19th October, Black Monday saw around15% wiped off global markets in one day.

In what many considered a surprise victory, John Major won the election with a 21-seat majority in what would be the last election for Labour leader Neil Kinnock, but also the last outright majority for the Tories for 23 years until 2015. As can be seen from the graph to the left, markets were slightly nervous of a Labour government perhaps, but recovered on Friday 10th April following Major’s victory. Once again, ‘nothing really to see here’. Thursday 9th April 1992 (2) Thursday 7th June 2001 (2) Thursday 5th May 2005 (2) Thursday 6th May 2010 (2) Labour’s first victory since 1979, saw Tony Blair win the first of his three elections with a massive 179-seat majority over incumbent John Major. This election would see the Tories in opposition for 13 years until 2010. Markets reacted but by the time of the day after, on Friday 2nd May, markets had become used to the likely outcome. No matter the historic size of the majority, in reality, a ‘nothing to see here’ election again in terms of markets.

Tony Blair’s second election victory saw the Labour Party’s massive majority cut, but only by 14 seats leaving a huge gap of 165 seats over William Hague’s Conservative Party. In terms of markets, as the graph to the right shows, 14th May saw a large fall, but it was nothing to do with the general election campaign called in the previous few days, but rather was caused by technical trading in US pharmaceuticals which impacted markets. UK markets recovered a week later.

By the time Labour had won, and the UK woke up on Friday 8th June 2001, the market had returned approximately to where it had started the election campaign. Markets wise, ‘nothing to see here’ again! Three months later however (albeit not as big economically as if felt at the time), the Twin Towers in New York were destroyed; the world was never the same again and ‘9/11’ as it became known, led ultimately to

the Second Iraq War.

In what would be Tony Blair’s last election, Labour won their third consecutive election for the first time in history, but with a reduced majority of 66 seats. Michael Howard, Conservative leader and a former Home Secretary, couldn’t capitalise on Blair’s unpopularity which had been significant since the Second Iraq War.

By 2007, both the Labour and Conservative parties had new leaders, Gordon Brown as Prime Minister (since 2007) and David Cameron was Leader of the Opposition (since 2006). With the Conservatives ahead in the opinion polls for the first time in fourteen years, 2005’s election saw the UK market end the campaign marginally lower than when it began; the first time this happened in the collection of the last ten elections under consideration. That said, by election day markets had virtually recovered back to where they had started the campaign. Press repeat… ‘nothing to see here.’

Although not known at the time, the 2010 election would be the first of four held in the decade; 2010, 2015, 2017 and 2019. In terms of the 2010 edition, the UK voted for what became the first official Coalition government since the ‘Lib-Lab pact’ in 1978. Tory leader David Cameron became Prime Minister and Liberal Democrat leader ‘What Nick said’ Clegg became Deputy Prime Minister, with Labour leader Gordon Brown exiting Number 10. The coalition resulted in a working majority of 38 seats.

In terms of UK markets, it was a definite ‘something to see here’ election. The political uncertainty caused markets to be nervous, seeing the UK market down over 12% on Friday 7th May, post-election day, when compared with when the campaign started. This was caused in the main by Coalition negotiations between the main parties not being finalised until Tuesday 11th May. UK Markets didn’t recover until late September, over four months later.

In the third consecutive election held in the month of May, and the second of four in the twenty-tens, the Coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, as expected, splintered. It also was the first of three elections under the rules of the Fixed Term Parliament Act, 2011, which had been brought in to reduce the uncertainty surrounding the 2010 election outcomes. And, although not really appreciated at the time, it would be the last general election before the Brexit referendum vote thirteen months later in June 2016.

n terms of the election itself, Prime Minister David Cameron was up against Labour leader, Ed Miliband, who in the Labour leadership that had followed the 2010 election, had defeated amongst others, his brother David. The Liberal Democrats were heavily punished by losing 49 of their 57 seats. The overall result saw the expected second consecutive hung parliament not materialise with the Tories winning a slender 10-seat majority. In terms of UK markets, uncertainty of the outcome resulted in markets generally falling in the month prior to election day. Once an overall majority had been confirmed on election night, markets returned to what they had been at the start of the campaign. Once again, a ‘nothing to see here’ election.

In the third election of the decade, and one that had been caused directly by the Brexit referendum result the previous summer, Theresa May replaced David Cameron as Prime Minister. Under the Fixed Term Parliament Act, this election wasn’t due until the summer of 2020 however due to the small majority of the government and the complexity and division of the ‘hardness’ of a Brexit deal, Theresa May felt that she needed a larger majority to see her vision of Brexit come to fruition. However rather than ‘strengthening her hand’, she was significantly weakened by the outcome which resulted in a minority government supported by the Democratic Ulster Unionists (DUP) to give the Tories a fragile working majority. Labour, led by Jeremy Corbyn, increased their seats by 30 which was one of the highest increases in seats in history by a political party who did not win the election.

In terms of UK markets, volatility had become the norm since the Brexit referendum. So although the outcome of the election wasn’t predicted correctly causing uncertainty, the morning the day after the election saw UK markets up from when the campaign had begun over four weeks previously. The election might have been interesting from a political perspective, but from the market’s standpoint, change had become the constant and markets had got used to uncertainty. Marginally a ‘something to see here’ election, but in the end, markets didn’t really care.

In the fourth and last election of the decade, Prime Minister Boris Johnson – who had replaced Theresa May in the summer of 2019 – called a snap election so he could ‘get Brexit done’. It was also the first UK general election to occur in December for 96 years and the only one in the collection of the last ten to happen outside the April to June quarter.

Jeremy Corbyn remained as Labour leader. In the middle of the campaign, the opinion poll difference narrowed between the parties, spooking UK markets. However, once it became clear the Tories would win, and with an 80-seat majority, markets were becalmed. On the day after, Friday 13th December, the market returned to marginally above its mid-November point when the campaign began.

Although there were periods of ‘something to see here’, at the end of the campaign, irrespective of party politics, markets once again confirmed their apathy towards elections when the outcome that had been predicted, happened.

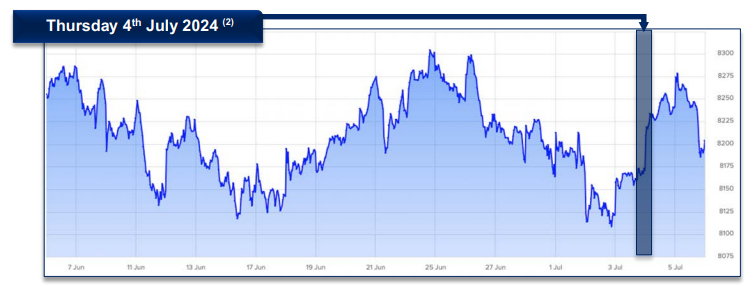

Now we’re up to date. As we know, Keir Starmer defeated Rishi Sunak with the biggest majority in nearly two centuries. In terms of politics, no matter your party affiliation, the writing seemed on the wall for the Sunak administration very soon after he took over from his predecessor, Liz Truss, who in turn was the shortest serving Prime Minister in history, serving only 49 days in the autumn of 2022. As discussed above, the Tories suffered one of, if not the worst, election day in their history. Only time will tell whether or not the Starmer led Labour administration fares better or worse.

In terms of markets, the apparent additional volatility above – i.e. additional ‘squiggles’ – shouldn’t be read into too much; it’s simply a function of the data being more recent and so the number of data points, i.e. the frequency of data supplied and captured, is more frequent, resulting in more ‘squiggles’ than the other graphs.

The key points are that by the end of the election campaign, the UK market ended virtually on the same figure it had started the campaign on. Albeit by now likely very tedious and repetitive, this again shows a nothing to see here’ election.

What should this tell you?

Using the UK as an example, out of the ten elections reviewed since 1987, the only election impacting UK markets was 2010. As we know that election was the most unpredictable election since the mid-1970s; and even then, it only took four months or so to recover back to its pre-election campaign position. The other nine elections saw markets either at parity or higher the day after the election. Based on this substantial evidence, at least in terms of the UK, and always remembering that past performance is no guide to future events, over the past 37 years, UK markets simply aren’t impacted by UK general elections.

Clearly however, UK elections have a minor impact on global markets. The US is a different story. But we can glean some assumptions for November’s US Presidential election based on the last ten UK general elections. If markets are expecting a particular outcome, and that occurs, then markets are apathetic, perhaps even disinterested. In effect, election results are ‘baked in’ to the markets. If outcomes are not what the markets expect, or there is uncertainty surrounding the election and its outcomes, similar to what happened in 2010 in the UK, then markets can be volatile, but even then, recovery is normally not far away.

When we consider the Trump v Harris election, based on current polling, it’s practically 50/50 who wins. That sounds uncertain making markets nervous. But, and it’s a big but, although personalities differ greatly, based on what is in the public domain currently, economic policy differences are minor, meaning markets likely would be apathetic.

Time will tell as ever. However, in the long-term, markets appear to not be impacted by general elections. Likely then, any investments you may have, over the medium-to-long-term, won’t be impacted either.

Sources

1) https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/

2) London Stock Market

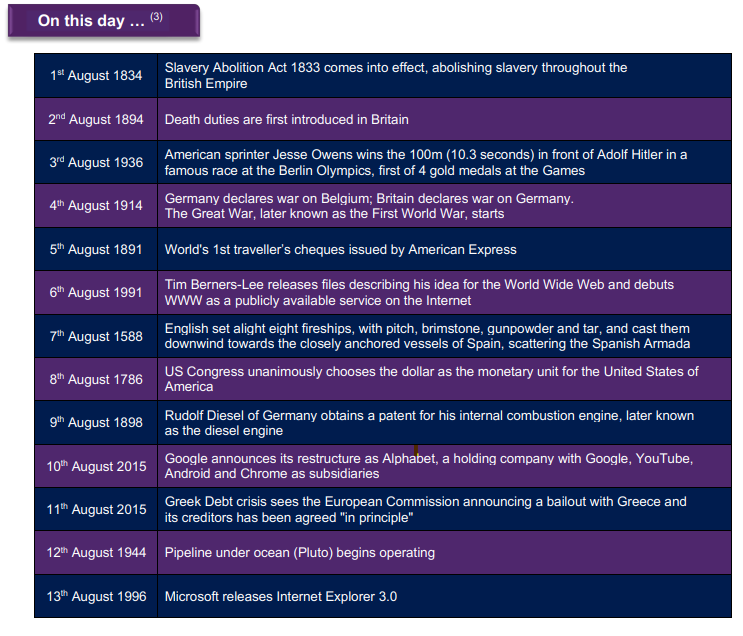

3) https://www.onthisday.com

If you’d like to arrange a meeting to talk to us about how to manage your finances effectively,

please get in touch. Email advise-me@fosterdenovo.com or book a meeting

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

The value of your investments (and any income from them) can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount you invested.

Foster Denovo Private Wealth is a trading name of Foster Denovo Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority Registration No: 462728.

Search

Search